In a Nutshell

- Michigan public schools saw more teachers retire last year than at any time in the past five years.

- These retirements happened against a backdrop of other longer-term challenges schools face in fully staffing classrooms.

- Michigan’s “critical shortage” listing of teaching positions has grown over the past five years with many more teachers leading classrooms they are not currently certified to deliver instruction.

With the new school year upon us, a number of school districts will be returning to full-time, in-person instruction for the first time since early 2020. Many students will be greeted by familiar school faces, including the dedicated, professional teachers anxious to return to in-person instruction after nearly 18 months of pandemic-induced learning. But, a surge of teacher retirements last school year, combined with a host of longer-term labor market trends, suggests many of these familiar faces won’t be there to greet kids on the first day of school. School staffing continues to challenge districts across Michigan.

In early 2019 the Citizens Research Council issued a report examining the teacher labor force in Michigan. Even before all the disruptions caused to public K-12 schools by COVID-19, the state’s educator workforce was already grappling with serious staffing issues in certain locales. While our report could not identify, document, nor quantify a general statewide teacher shortage, we highlighted a number of troubling trends in the underlying data to support what many districts across the state were experiencing: on-going challenges to fully staff certain schools, individual positions, and specific classrooms.

The pandemic altered so many aspects of how people work and transformed the broader labor market. This is true of public education too. But, entering the new 2021-22 school year, we don’t yet know the pandemic’s full effects on the state’s K-12 education labor market. With the start of a new school, public attention is beginning to focus on classroom staffing challenges. So, we wanted to examine the longer-term trends associated with the demand for, and supply of, public school teachers. We highlight key themes addressed in our 2019 report with updated data and analysis to provide a broad picture of the public K-12 education workforce.

Spike in School Retirements

Michigan public schools employ roughly 338,000 people across all positions, from classroom teachers to paraprofessionals to food service. Each year, a number of them leave public education for a variety of reasons, including retirement. The recently completed 2020-21 school year (ending June 30) saw the largest number of retirements in the past five years.

According to data provided by the State of Michigan, 7,262 individuals in the state-run school employees retirement system (MPSERS) retired between July 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021. This represents a 16 percent increase over the previous school year and 900 more retirements than occured in the 2016-17 school year. (Note: Approximately one-half of the public school workforce are members of MPSERS).

Classroom teachers make up about one-third of the workforce, the second-largest category of school personnel statewide. Similarly, teachers accounted for 30 percent (2,087 retirants) of all MPSERS retirements last year. Again, a sizable jump (17 percent) from the previous year’s total. Many observers have suggested that the school and classroom disruptions caused by the pandemic (shifting between in-person and remote learning, increased safety precautions) drove the spike in school retirements last year. New monthly data suggest that this might be true.

The chart below tracks the year-over-year changes in teacher retirements by month. It is notable that the monthly retirements in the 2020-21 school year exceeded the previous year in all but three months (April to June).

Year-over-Year Teacher Retirements by Month

Source: Office of Retirement Services

Historically, July accounts for the majority (50 to 60 percent) of the total annual retirements. This is because many eligible employees, who have qualified for the state retirement benefits and completed the school year, make their employment plans for the upcoming fall at this time. A spike in teacher retirements clearly shows up in the July 2020 numbers; months after all Michigan schools were forced to shift to remote learning in the Spring of 2020. Monthly retirements continued to rise into the winter months. In fact, within the first seven months of the 2020-21 school year (January 2021), the cumulative number of retirements (1,797) had surpassed the 12-month total for the previous year (1,777).

The state’s July 2021 monthly retirement figures show 941 teachers retired, a large drop from the 1,153 individuals that called it quits last summer. This was the first time in the past six years that teacher retirements fell below 1,000 in July. While it might be too early to say how the rest of the year will shape up, historically the July numbers drive the yearly total. Regardless, last year’s record number of teacher retirements has altered the workforce.

Longer-Term Challenges

The increase in public school employee retirements last year occurred against a backdrop of existing staffing challenges on both the supply- and demand-side of the workforce equation. These challenges, many touched upon in our 2019 report, are confirmed in the latest data released in the Michigan Department of Education’s annual Educator Workforce Data Report. This report provides a bevy of information and raw data related to the state’s educator workforce, touching upon all aspects of the educator pipeline from teacher preparation to certification to professional development and more.

One key take-away from the updated report is the worsening of the state’s “critical shortage” position list. According to data collected by the state and shared with the U.S. government, Michigan’s federally-designated educator shortage list has expanded in scope (more types of positions covered) as well as in depth (number of positions) over the past five years. It should be noted that this listing does not represent actual open job postings within a state, but instead signals subject areas in which a state is having a difficult time filling positions. The list is used by the federal government for purposes of student loan forgiveness/deferment for those individuals that take teaching assignments within a shortage area.

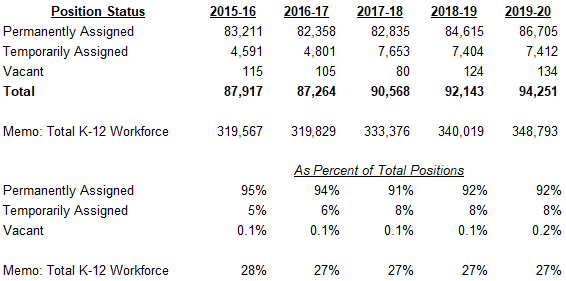

The most recent report confirms our earlier finding that shortage positions are primarily concentrated in career and technical education, special education, elementary education, and social workers. The table below shows the number of critical shortage area positions reported to the state each of the past five school years; it breaks the data into 1) positions filled by individuals permanently assigned and certified to teach a subject, 2) positions filled by individuals temporarily assigned and NOT certificated to teach a subject, and 3) vacant positions. Positions identified as “critical shortage” represent 27 percent of Michigan’s total K-12 public education workforce, a fairly consistent share over the past five years.

Federally-designated “Critical Shortage” Positions

Source: Michigan Department of Education

The number of positions designated on the shortage list (“Total” in table) grew from 88,000 to 94,000 – a signal that 1) more and more schools are finding it difficult to fill positions in the covered areas, and/or 2) the expansion of shortage to other classrooms and positions. Additionally, the number of teachers assigned to work in a classroom for which the individual is NOT certified to teach has grown from five percent to eight percent of the total shortage positions. So, while these shortage positions are filled with certificated teachers, those individuals don’t have the appropriate subject-level training and licensing. For instance, a school might have to assign a middle school math teacher to teach in an elementary classroom.

Michigan public schools were already struggling to get classrooms fully staffed with qualified and properly-credentialed employees. The recent spike in retirements, spurred in part by the pandemic, will further strain schools’ staffing efforts for the upcoming school year. Fortunately, public schools will have the resources the tackle these challenges thanks to the record-setting infusion of federal aid and a healthy state school aid budget.

Permission to reprint this blog post in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided that the Citizens Research Council of Michigan is properly cited.